Good posture —it seems everyone is talking about and searching for it; from the millennials who are sitting all day in front of computer at their workplace, to the older adults wanting to stay fit and functional. A simple search on the internet and you will be inundated with “cures” on how to get good posture as well as a plethora of approaches by many different kinds of health advocates.

Many health practitioners from traditional to alternative medicine advise us on the importance of good posture. It helps us breathe more deeply, lessens back and neck pain, reduces risk of falls, helps in injury prevention and helps us function better in our daily lives.

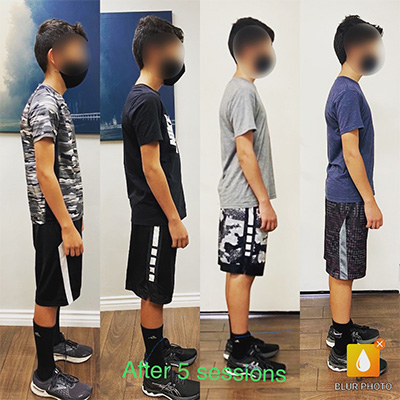

In recent years there has been a proliferation of books, videos, and blogs on how to correct posture as well as numerous exercise systems and postural devices. There are even clinics throughout the country that specialize on how to build correct posture with a promise of back pain relief. The pandemic has further increased our already sedentary lifestyle fueling the desire in learning how to “straighten up”. But the problem still exists, in fact, poor posture and back pain as well as back surgery continues to rise. The number one question I receive on social media is about how to create good posture and surprisingly, many are in their 20’s and 30’s. It is apparent that poor posture is affecting an increasingly younger crowd.

Muscular Approach

Many different kind of clinicians and health practitioners address posture: chiropractors, physical therapists, personal trainers, massage therapists, yoga teachers, pilates teachers etc. Most of these practitioners approach posture from a muscular standpoint; lengthen tight muscles and strengthen weak ones to support a more upright postural position.

A typical scenario. You have a forward head posture and your shoulders are slumped, you go to a health practitioner who says your posture is caused by weak muscles and gives exercises to retract the shoulder blades and stretch your opposing pectoralis muscles. You make a sincere and concerted effort to keep your shoulders back when sitting and standing, but cannot keep it up as it tires you. So you simply go back to your previous slouched forward head posture.

Scenario number two. Your low back is rounded, your head protrudes forward as does your shoulders. You are told to use the cue of visualizing you are being pulled up from the top of your head. You try this for awhile until you realize there isn’t a huge difference, so you give it up and go back to your old posture.

I call these techniques to correct posture “the muscular approach.” The theory is that if the right muscles are strengthened, and tight muscles lengthened, it will result in good postural alignment. I found this approach ineffective because the pelvis, the foundation of the spine, is not being addressed. The position of the pelvis sets up the stage for what will happen to the thoracic and cervical curvatures of the spine. If the foundation of the spine is not neutral, the shoulders and neck can never get into a good position.

And it is missing visual imagery — imagery helps secure keep the entire skeleton and reinforces its good vertical position on a daily basis.

Think of the frame of the house (skeleton) being set before adding reinforcements (muscles). By placing the bones in good position the muscles will naturally follow. In contrast, stretching and strengthening muscles first without the body knowing where correct postural alignment should be, means the body will not know how to anchor its skeleton into neutral spinal position. It will not know how to securely build the frame (skeleton) before adding reinforcements (muscles).

In the muscular approach, it is assumed that by strengthening and stretching the right muscles posture will naturally come back in line. But that doesn’t work. Someone who has been in a poor postural position for a long time isn’t going to know how to find, or feel a natural and upright neutral position simply by tightening and strengthening muscles. They won’t know what that looks or feels like for their body. They won’t know where to reset the body so they often go into an overly arched back, flaring their ribs, which in turn tightens the low back muscles.

Skeletal Approach

There needs to be a skeletal guidepost; a framework, a template, an anchor point, a blueprint, enabling one to know how to go about self aligning the skeleton using tactile technique and visual imagery. The “skeletal approach” provides this powerful guidepost. It immediately helps anchor a new postural position. It is a simple method that can be easily integrated into daily life. The skeletal method consists of two parts, the visual and tactile anchors.

First the visual anchor. The first step in teaching the “skeletal approach” is by showing the skeleton and the importance of the rib cage being in good neutral alignment over the pelvis. I ask students to envision the pelvis as one cylinder and the rib cage aligned directly above as another. It helps to bring the body back to the posture plumb line, where gravitational forces are distributed evenly throughout the body, creating ideal skeletal alignment.

Imagery is one of the most powerful daily tools that can be used to create new neuromuscular pathways and train proprioception. It is crucial in maintaining and integrating a new postural form into the nervous system.

Next, aligning the rib cage over the pelvis with a tactile anchor technique. I have the student put their hands on their hips to feel their pelvis in neutral position, then I have them put their hands on their rib cage and do the same. Are they perfectly aligned one above the other? This is a great tactile tool they can use anytime. It gives the student a tool for self-correction.

This technique is indispensable in helping students find good alignment throughout the day. It gives the student a tool to quickly remind the nervous system of a better body alignment. This repetition makes the new habit of straighter posture more quickly integrated into the nervous system.

Once the pelvis is in neutral position with the rib cage above it like two perfectly stacked soup cans, the shoulders and neck will as a matter of course, fall back in proper position without strain. The shoulders and neck will not have to be forced back causing pain and discomfort. A huge benefit and effect of establishing a solid base with the pelvis and ribs in neutral position, is that it will be difficult for the neck to drift forward. It will almost feel like the head and shoulders are somewhat locked into place and cannot be protracted without intent.

This skeletal approach gives a clear skeletal guidepost and image of what to aim for in achieving good posture. Unlike the standard muscular approach which may seem nebulous with its suggestion for “stand up straight,” the skeletal approach gives a tactile and visual anchors. The student sees the skeleton, feels their own bones and knows what to aim for. This enables them to self-correct during the day, making the process of assimilating good posture quickly absorbed into daily life. Adding the visual imagery of two stacked cylinders further reinforces and integrates a new postural position.

The “skeletal approach” is empowering. It is a simple and doable technique that can be done during the day, makes sense and bears immediate results. Through over 20 years of experience in the fitness and rehabilitation, I have found this “skeletal approach” the most effective and efficient way to help students find good postural alignment. One that is they can retain, reinforce and integrate into their daily lives